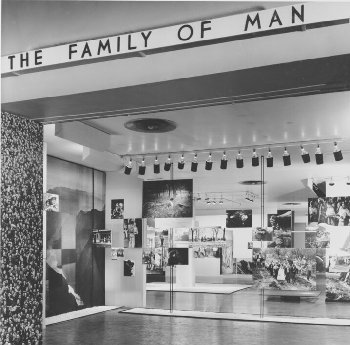

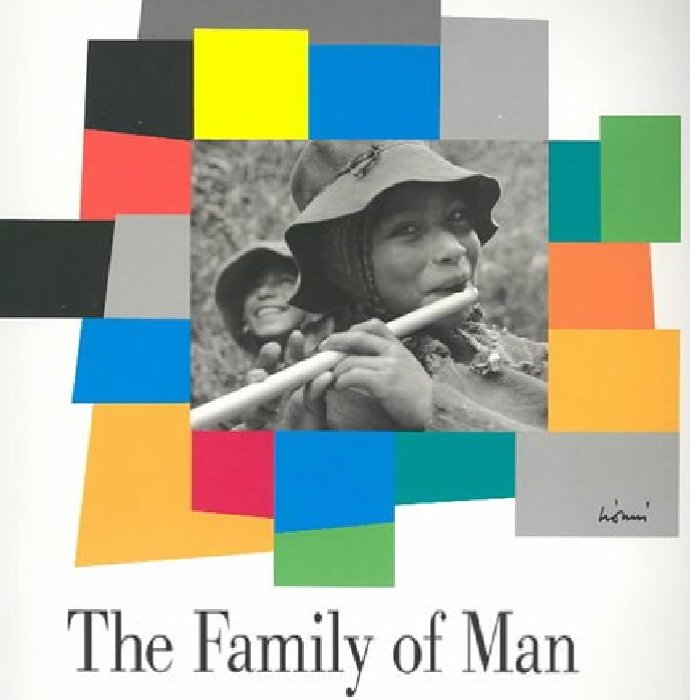

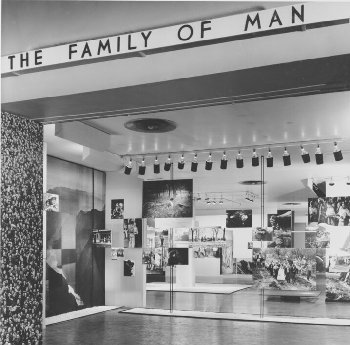

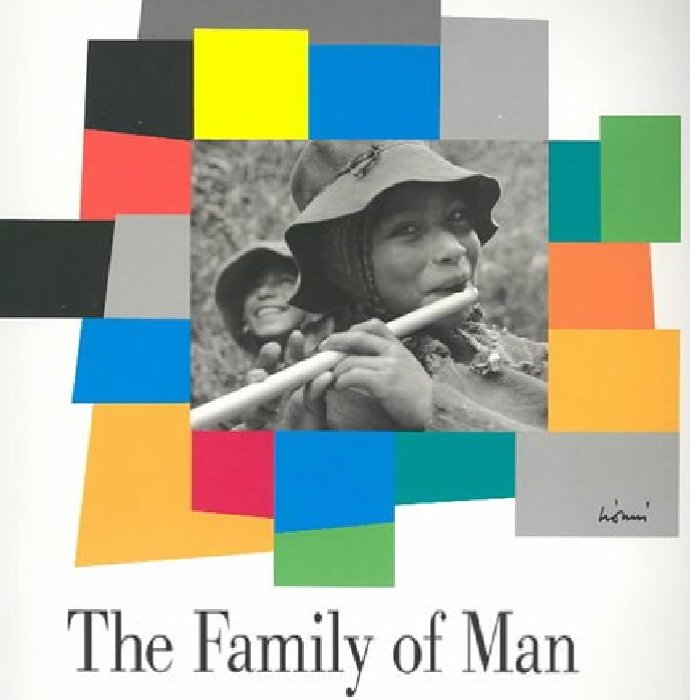

Family of Man exhibition entrance and graphics from The Family of Man exhibition book

HISTORY | STORIES | BEYOND BLOG & CREATE PEOPLE |

In April 1959, thousands of Sydney-siders visited the David Jones Gallery in Sydney City to view a groundbreaking photographic exhibition called " The Family of Man" which had been touring the world since its first opening in New York in 1955. It presented images of people from around the world and aimed to show the idea of the common origin and unity of the human race.

Ambitious Project

"The Family of Man" was an ambitious project of 503 images from 68 countries. A precursor of today's "blockbuster" traveling exhibitions', at the time it was the th largest photographic

exhibition ever mounted. It was devised by the director of New York's Museum of Modern Art's (MOMA) photographic department, Edward Steichen (1879 - 1973).

He was assisted by Wayne Miller and the exhibition designer, architect Paul Rudolph.

Steichen and his staff reviewed many existing image collections and wrote to photographers from around the world seeking suitable photographs. They distilled two million available images down to just 503 in an effort to build an exhibition that could portray theuniversality of the human experience.

The exhibition first opened at MOMA New York January 24th 1955 and continued there until 8th May 1955. It then toured cities around the world to record breaking audience numbers. The newly formed United States News and Information Service managed the traveling exhibition. With the backing of the Service and input from MOMA, it had the most professional and cutting edge display and curatorial technology available, giving it a slick presentation that could "wow" audiences.

Two Australian Photographers

Two Australian photographers were included. Lawrence Le Guay(1916 - 1990) had an image showing courting rituals from the Waghi Valley in New Guinea.

David More (1927 - 2003) had an image taken in the working class inner-Sydney suburb of Redfern. It showed a young woman in bed with her new-born baby. At the foot of the bed stood an older woman, presumably the younger woman's mother, deep in thought rather than paying attention to what should have been a joyous occasion. A young child plays with a toy on the floor near the foot of the bed. The image speaks of tension, concern and poverty. Where is the celebration of the birth? Where is a male figure? Moore would later explain that the family was indeed in dire straits and facing eviction the next day.

The viewer may have been left with the impression that this was the general condition of all Australians - no doubt some Australians may have felt that in fact was the reality at the time.

Coming to Australia

In 1958 a voluntary group called the Citizens' Welfare Services of Victoria suggested that bringing the exhibition to Australia would be a good opportunity to raise funds for voluntary organisations.

After a year's negotiation with US officials, starting with the US Cultural Attache in Melbourne, it was finally agreed that the copy of the exhibition that was due to finish in Montevideo, could make its

way to Melbourne arriving on February 13, 1959.

American authorities paid for the freight to and from Australia, but other costs had to be borne by the voluntary association set up to manage the exhibition's progress throughout Australia. It was estimated that these costs would amount to £25,00. Architectural work, staffing, services and materials were reduced to a minimum by voluntary import, meaning that the committee only had to contribute around £10,000. Proceeds from the entry fees charged for entry to the exhibition were distributed amongst each of the four state charities in whose capital cities the exhibition was held.

The exhibition weighed 5 tons and a special pantechnicon was built to transport the exhibition. It needed 10,000 square feet of display space - in those days there were fewer Australian public venues that could accommodate it. For this reason, in Sydney, it was hosted by the department store David Jones Gallery, one of the few large exhibition spaces in Sydney. The other cities also used commercial spaces. Someone suggested that it was only fitting that the artistic product of American materialism should sit along the shiny new automobiles of Melbourne's Preston's Motor Show Rooms.

After Melbourne, the exhibition opened in Sydney, and it then travelled to Brisbane, Adelaide. The dates and locations were:

The exhibition never made it to Western Australia, although early publicity suggested that there were also plans for an exhibition at a Perth venue.

Reception in Australian

The idea of a universality of the human experience, though not a particularly controversial notion in Australia at the time, was nonetheless thought provoking at a time when Australian

social policy was underpinned the "White Australia Policy". The underlying notion of a global citizenship and its advocacy of human rights, did not sit well with Australia's then restrictive

and discriminatory immigration and social policies, perhaps part of the movement to to shift public opinion away from the then exclusivist, isolationist immigration policies.

The Family of Man clearly had a lasting influence on Australian photographers who saw it, cementing a model of humanistic documentary photography that was to dominate practice of the 1960s and beyond, in which photography was understood as a universal language able to communicate simply and directly across barriers of race and culture.

The influence of the Family of Man encouraged a collective of Melbourne-based amateur photographers Group M to hold the first of a series of annual exhibitions titled Photovision at the local Museum of Modern Art in a cobblestone lane off Flinders Street less than two months later in 1959. Advocating the use of ‘straight’ photography as a means of expression, Group M presented an exhibition, Urban Woman, at the Lower Melbourne Town Hall in 1963. Perhaps influenced by the superlatives that described the Family of Man exhibition, they described it ‘the most ambitious exhibition ever to be attempted by a group of Australian photographers’, it featured around two hundred candid photographs by thirteen photographers.

Australian photography had moved away from reliance on portraiture and artistic themes to realist depictions of contemporary social issues and themes.

Criticism

Popular acclaim for the exhibition centred on the humanistic values it perceived as being expressed by the exhibition. The universality of humankind was seen as a positive and empowering message ,

as the "Rambling Rose" correspondent from the Port Lincoln Times put it:

Students of their fellow humans spend hours viewing the excellent display of photographers' art, representative of all classes, creeds and conditions of humanity from every corner of the earth.

This was generally at odds with scholarly criticism. The exhibition, it was argued, took individual photographs out of context. It featured the work of mainly male, European photographers, outsiders who lacked an understanding of their subjects. Or that it expressed, even if only subtly at times, the dominant western values, colonialism and racism.

The French philospoher and critic Roland Bathes is the most often quoted critic of the exhibition. His reaction after viewing it in Paris was that it showed an essentialist view of human experiences such as birth, death, and work, and the removal of any historical specificity from this depiction.

Later Allan Sekula (1951 - 2013), the American photographer, theorist and critic, viewed the exhibition as a populist ethnographic archive, the epitome of American cold war liberalism that universalized the bourgeois nuclear family and therefore an instrument of cultural colonialism.

The most dramatic "criticism" of the exhibition was by Theophilus Neokonkwo, a Nigerian man, a student studying in Moscow, who slashed and tore down prints by Polish-born American Life photographer Nat Farbman (1907–1988). Neokonkwo objected to the depiction of non-Europeans, especially Aficans as "either half clothed or naked and as social inferiors, as victims of illness, poverty, and despair, while white Americans and Europeans were represented mostly in dignified cultural states: wealthy, healthy and wise".

Lasting Value

The Family of Man achieved its central role in the history of twentieth century photography largely because of its international exposure. Ten different versions of the show were seen in 91 cities in 38 countries

between 1955 and 1962, viewed by an estimated nine million people.

In 2003, the Family of Man photographic collection was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in recognition of its historical value. A permanent installation of the exhibition is now on display at Chateau Clervaux in Luxembourg (the country where Edward Steichen was born), and follows the layout of the first exhibition at MoMA though it has beens adapted to fit into the two floors of the restored Castle.

References

Copyright © Coogee Media All rights reserved

|

|

| CONTACT US | ABOUT US |