Shark Attack - Coogee

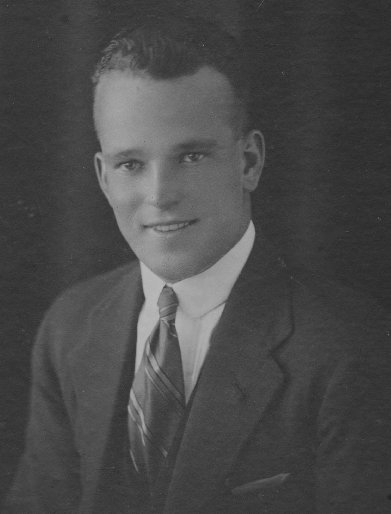

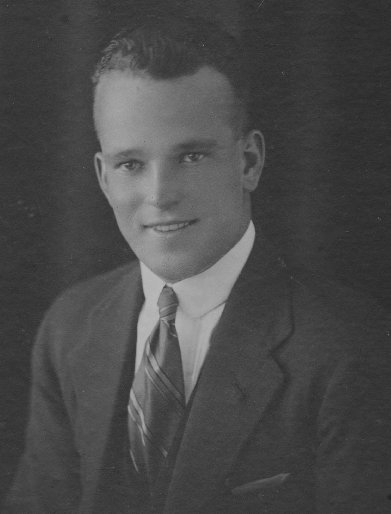

Milton Coughlan

Milton Singleton Coughlan was an 18-year-old local boy, an active surfer, and member of the Coogee Surf Club. He was described as a fine, sturdy, bronzed youth,

with the physique of a grown man. Only the week before, he had rescued a drowning man at nearby Maroubra Beach. He was the second son of Thomas Coughlan,

the Randwick Postmaster, and the great-great-grandson of Benjamin Singleton after whom the township of Singleton, NSW was named. His address at the time

was given as Post Office, Randwick, likely living with his parents in the Postmaster's residence.

Milton worked for the NSW Railways at Newtown. He had attended school at both Sydney Grammar and Trinity Grammar where he had shown considerable athletic prowess.

Perfect Day for Surfing

Saturday February 4, 1922 at Coogee was turning into what should have been a perfect day. It had been cloudy much of the day, but the sky cleared,

and it was becoming a light, sparkling sunny day. The air temperature was 26°C and the water was 23°C.

There were long rolling breakers that carried to the shore. About 6000 people had gathered on the beach to watch a surfing

carnival, but it had not yet started. Who could resist swimming at Coogee Beach?

Milton Coughlan

The Shark Attacks

At about 3.30pm, Milton Coughlan

got down on the rocks near the Coogee Surf Club house and swam into the area known as the reef about 30 meters out, and began catching breakers. He was with two

friends; C. Britnall (see note 1) and R. Ferguson. One of the friends called out to him to watch out for sharks in the channel, and Coughlan laughed, apparently not

appreciating the real danger he was in. But then, standing in the water, he saw the shark and shouted a warning to the other

body-surfers. While he was swimming ashore, the shark struck him with 'great violence'. As Coughlan signalled to his club-mates for help, the shark grabbed his

arm and momentarily dragged him beneath the waves. Moments later he reappeared above water, and spectators saw him pummelling the shark with his left arm, but

then the shark took his left arm in its jaws. The water was red with blood and horrified onlookers yelled in alarm.

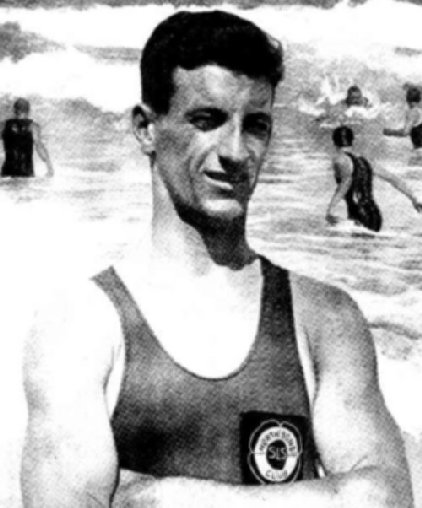

Jack Chalmers, a member of the North Bondi Surf Life Saving Club, saw Coughlan's plight. He rushed down the rocks near the clubhouse and hastily tied a line

round his waist. As he scrambled over the slippery green rocks, he fell and his leg was badly cut. Struggling to his feet, he plunged into the water and

together with Australian Olympic swimming champion Frank Beaurepaire (1891 - 195), brought Coughlan to shore on the rocks near the club from where a number of sharks

could be still seen circling in the water.

Terrible Injuries

Coughlan had suffered terrible injuries. Those on the shore gave him first aid and applied a tourniquet to his wounds. Luckily, an ambulance station

had only recently been established half a block away at Arden Street, and an ambulance took him to Sydney Hospital, then the nearest major hospital to Coogee.

Dr. Ramsay Sharp recorded that the patient "as unconscious on admission, his colour being very pallid, respiration slow, pulse just palpable, and reflexes absent." He

died in the hospital at 3.55pm of shock and just 25 minutes after the attack.

Heroes Recognised

Both Chalmers and Beaurepaire were feted as heroes and awarded medals from the Royal Shipwreck Relief & Humane Society of New South

Wales and the Surf Life Saving Association of New South Wales. They were also rewarded with £500 each.

Beaurepaire later said that he received all up about another £700 from public subscriptions. Beaurepaire went on to enjoy successful careers in swimming, sports administration,

business and politics. He represented Australia, again at Olympic swimming, at the 1924 Paris Games. He used his money to start a national business, Beaurepaires Tyres, and was

eventually knighted and became Lord Mayor of Melbourne from 1940 to 1942. He was a member of the Victorian Legislative Council from 1942 to 1952.

Jack Chalmers was also awarded the Albert Medal, the highest decoration for bravery given to a civilian. Jack Chalmers' life after the 1922 shark attack was not so successful as that of Beaurepaire's. There

were varying reports about how much money he had actually received. A public benefit subscription was said to have raised Chalmers another £2,500, according to some press

reports. In relative terms, whatever he received, was then a huge amount of money. He used some of the money to buy a property for £1,200 in the nearby suburb of Kensington, which he rented out, and

he started a trucking business. In April 1934, it was reported that Chalmers and his wife and two children had been overwhelmed by the tide of the economic depression and he had to declare himself bankrupt.

His Sydney to Bathurst freight run could not compete with the railways and was liquidated. His Kensington property was no longer paying rent and he owed £370. Instead of being a

self-employed businessman, he was employed as a driver for an oil company.

In March 1943, Chalmers stood trial on a charge of stealing petrol, presumably a fairly serious matter in those times of wartime rationing. In defence of his character to the Court, he stated that

he had sent an unsolicited cheque for £500 to Frank Beaurepaire in 1922 to even out the amounts collected by the public benefit subscriptions. Beaurepaire, however, would have none of it -

"I desire to make it clear that at no time have I ever received money from Jack Chalmers in connection with the Coogee shark rescue." In addition to earning the enmity of old comrade in the

shark rescue, it was reported that he was sent to gaol, presumably meaning he was found guilty as charged.

Despite the travails he suffered over the decades, Chalmers continued to be remembered as the hero of the 1922 shark attack at Coogee. In 1971 when it was decided to replace the Albert Medal,

owing to the decline in its status, with the George Cross and living recipients would be invited to exchange their medals. Chalmers was one of six Australian Albert Medal recipients who opted to accept the medal

offer. He received the new medal at an investiture by the Queen at Buckingham Palace in London on 12 July 1972. Chalmers retained his affiliation with the Surf Life Saving Association for the rest of his life,

later being presented life membership. Chalmers was employed as an ironworker, and later a rigger, at the Balmain shipyards. Chalmers died at his home in Bondi Junction on 29 March 1982, aged 88 and

his ashes were scattered on Bondi Beach. Chalmers, a World War One veteran who joined the AIF in 1915 and served on the Western Front as a medical orderly, has his campaign medals and George Cross

in the collection of the Australian War Memorial.

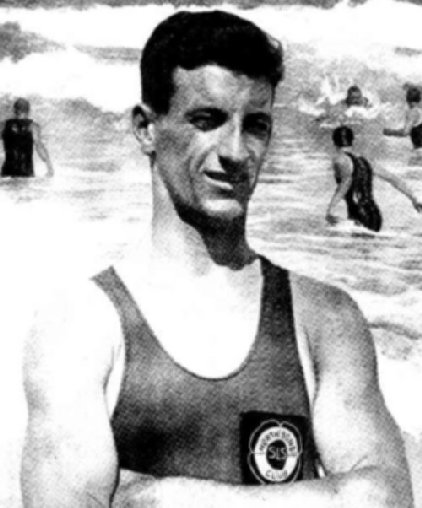

Frank Beaurepaire, Melbourne Lord Mayor

|

John "Jack" Chalmers, GC (1894 – 1982)

|

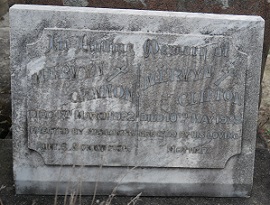

Coughlan Buried at Randwick General Cemetery

Coughlan's well attended funeral service was at St. Judes Anglican Church in Randwick. He was buried in Randwick General Cemetery in South Coogee. An

inscription on his grave by the British poet Richard Molesworth Dennys (1884 - 1916) reads:

Come when it may, the stern decree

For me to leave the happy throng

Of comrades whom I have lived among.

No need for me to look askance

Since no regrets my pathway mars,

My past was happy and perchance

The coming night is of full stars.

|

Time has taken a toll on Milton Coughlan's Grave

|

Coogee Live Saving Club Crest

on Milton Coughlan's Grave

|

Tragically, Milton's father Thomas also died violently in 1939, at the age of 74, when he tried to stop two robbers from raiding the Randwick Military Hospital

Post Office, where his widowed daughter worked as the Postmaster and he worked part-time. He was beaten over the head with a pistol and died later in

hospital from his injuries. He was buried in the same plot as his son.

Second Shark Attack

Then came the shocking news of another attack. On Saturday 3rd March 1922, 21 year old Coogee local Mervyn Gannon was attacked in relatively shallow water

on a crowded Coogee Beach. Gannon was variously described as an engineer, motor engineer and motor driver. He is likely to have worked in a motor

repair shop. He lived in the Normandy flats in nearby Vicar Street, which one press report described as being on the corner of Belmore Road (now

Coogee Bay Road) and Vicar Street.

Beach Inspector J. Brown and Ernest Carr rushed into the water to save Gannon and brought him to shore. The young man had terrible injuries, having

lost a hand and fingers and gashes to his body. His condition seemed critical but, nonetheless, he was rushed to St Vincent's Hospital.

Surgeons struggled to save him, but he died the following Sunday morning.

After another well attended funeral, this time in the city, a large cortege, including a squad of NSW Mounted Police escorted the coffin to Randwick General Cemetery.

Mervyn Gannon was buried in the Roman Catholic C section, plot 116.

To make matters worse, a public brawl erupted about who had waded into the surf to rescue Gannon, and whether, in fact, anyone had actually lent a hand.

Several enquiries followed, including one by Randwick Council, which vindicated Inspector Brown and showed he did all he could to save Gannon.

|

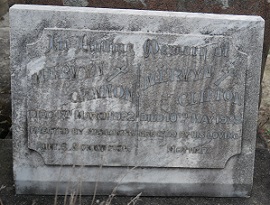

Headstone at Randwick General Cemetery, reads:

In loving memory of Mervyn Gannon.

Died 4th March, 1922.

Erected by his loving aunt S. Bonnington

In loving memory of Mervyn Clifton.

Died on 10th May 1928.

Erected by his loving mother

|

Huge Public Interest

Understandably, many people were reluctant to venture into the surf for some time. The spate of shark attacks at Coogee was sensational news in Sydney and caused great attention, almost ghoulish interest, from the public who flocked to

Coogee over the coming weeks.

On the Sunday following the attack, it was estimated that 70,000 people gathered on Coogee Beach in the hope of seeing the deadly shark which made the

attack, being caught by one of the many knife-wielding divers or shark hunters who set out to catch and kill the shark. There was even one proposal, rejected, to

bomb the bay in an effort to rid Coogee of sharks.

Huge Crowds Gather at Coogee Beach

Macabre

Over the following days, a number of the beasts were caught and hauled ashore to be displayed to the crowds. Two men caught one animal and after erecting

canvas shields around it, charged the public to file through and view its corpse.

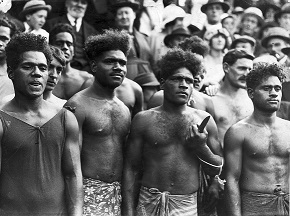

New Caledonian Sailors Have a Go!

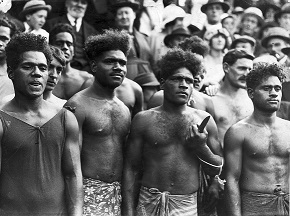

On March 12, 1922, 12 members of the crew of a freighter docked in Sydney harbour made their way out to Coogee to try their hand at catching the sharks. They

were native inhabitants from the Loyalty Islands of New Caledonia. These young, fit, good looking men claimed to have had some

experience with wrangling creatures of the deep. With knives clutched in their

teeth, they caused a sensation in Sydney, and by some accounts, 80,000 people gathered on all of Coogee's vantage points hoping to see them catch and kill the

sharks. The Islanders swam out to baits suspended in kerosene tins. Varying reports say they did not sight any sharks, others that they did kill and retrieve a shark.

No matter, the crowds loved the sport, if not the memory of the victims.

New Caledonian Sailors at Coogee Beach Ready to Meet Sharks

Shark Caught at Coogee Beach, c1929

Another Shark Attack

Just three years later in March 1925, another shark attack almost claimed the life of another younger surfer, Jack Dagworthy, but he fortunately survived with the

loss of a leg. Read more about the 1925 Shark Attack here.

References

Weeks, Richard D. Global Shark Accident File (http://sharkattackfile.net/spreadsheets/pdf_directory/1922.02.04-Coughlan.pdf accessed 11 July 2021)

'Fight with a Shark: Tragedy at Coogee', Sydney Mail, Wed 8 Feb 1922, Page 10

Collins R. M., 'Tales of Frank Beaurepaire - Acts of Heroism that Thrilled Australia', Sporting Globe (Melb.) Wed. 11 Jan 1939, p. 15

Dick Whitaker, http://passingparade-2009.blogspot.com/2011/04/shark-attack.htm (accessed 12 July 2021)

Vockler, Alf, 'Sydney Surfers Paid Big Rewards for a Man-eater', Sydney Morning Herald, 14 Dec 1969, p. 63

'Obituary [of Thomas Coughlan]', The Sydney Morning Herald Sat 19 Aug 1939, Page 19

Cripps, Ian, Randwick General Cemetery Historical Monograph No. 4, Randwick & District Historical Society, 1986, p. 26

'Coogee Tragedy', Warwick Daily News, Mon 6 Mar 1922, Page 2

'Death of Mervyn Gannon' Singleton Argus, Tue 7 Mar 1922, Page 3

'Snatched from a shark's jaw', Young Witness (Young, NSW) Sat 4 Mar 1922, Page 1

'Hero of the Surf Bankrupt', The Labor Daily (Sydney), Tue 17 Apr 1934 , Page 8

'Shark Hero' National Advocate (Bathurst, NSW) Tue 17 Apr 1934 , Page 2

'Was not given £500 by Shark Rescue Companion', The Argus (Melbourne) Thu 18 Mar 1943, Page 3

Maguire, Anthony 'Coogee Surf Club Restores Shark Victim Memorial' The Beast, February 2022, Issue No 205, p.22

Note 1: He may have been the Charles Britnall who took over a fish and chips shop at 233 Coogee Bay Road, Coogee in the 1930s.

Note 2: Coogee Surf Club has recently raised $5,000 to mark the centenary of the shark attack on Milton Coughlan. The project has brought the damaged headstone and obelisk on the grave of Coughlan

and his parents at Randwick General Cemetery back to its original condition. The gleaming white marble memorial stands out boldly among other memorials, in stark contrast to the damaged and colourless

stones that previously marked the grave.

Milton Coughlan's restored memorial

| |

Copyright © Coogee Media All rights reserved

|